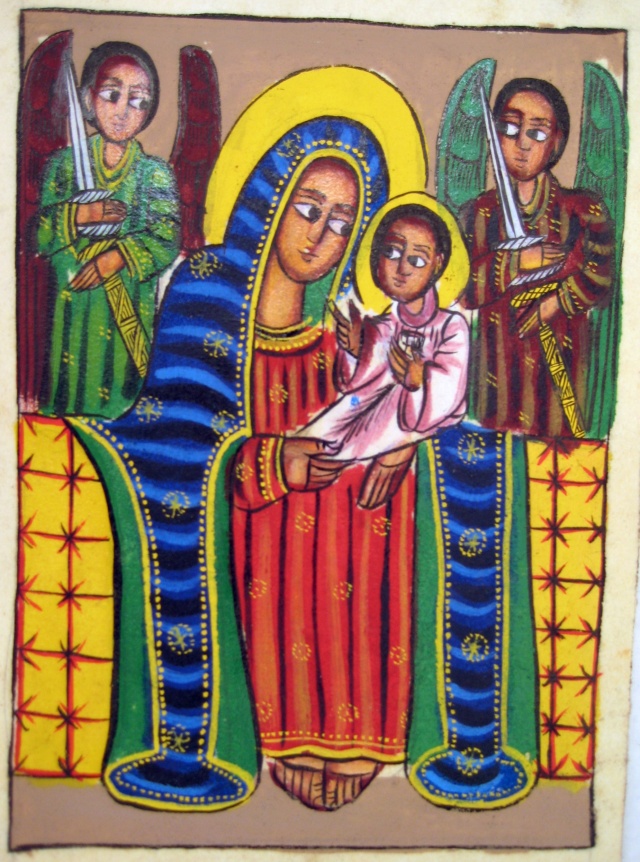

Mary and Jesus with Archangels (similar to a piece from the exhibition)

This past Saturday I was asked to give a talk on Ethiopian Orthodox Church art for an exhibition that has been going on since March at our church. Though I have training in Museum and Gallery Studies, and especially art with my Art History undergraduate degree, I had never actually given an art talk. So it was both nerve-wracking and exciting for me, and I spent about three weeks researching the topic (which was rather complicated and hard to summarize, but everyone in attendance seemed to enjoy it). A parishioner and member of the church committee that I’m a part of called Faith Through the Arts, allowed us to use her pieces for this first exhibit. They consisted of Ethiopian Orthdox Church icons on wood and goatskin that featured brightly colored images of the Virgin Mary, Jesus and the Apostles, St Gabriel and St Michael and the Tinity, amongst others. Below is the paper I wrote for the art talk.

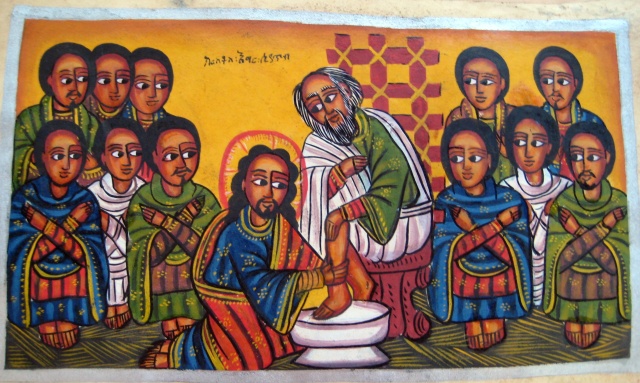

Jesus Washing the Feet of His Disciples

The History of the Eastern Orthodox Church and Its Icons and Crosses

Ethiopians became polytheistic starting in the first millennium BCE. Around 960 BCE the Queen of Sheba visited Jerusalem and met the famous King Solomon. When she came back to Ethiopia, she bore him a son. Once the son got older, he visited Jerusalem and brought back Levites (who were in charge of religious duties in the city) and supposedly the Ark of the Covenant (which held the 10 Commandments). “A replica of these tablets, known as a Tabot, is placed in the Holy of Holies [what we refer to as the sanctuary] at the heart of each Ethiopian Orthodox church building.”[1]

Christianity became the official religion in the 4th century CE. However, there were Christians there much earlier than that. “In the Acts of the Apostles, [Chapter] VIII: 26-40, we are told of a certain Eunuch, who went with the treasures of Queen Candace of Ethiopia, to Jerusalem to worship the God of Israel. There he met Philip the Deacon and was baptized by him. Ethiopian tradition asserts that he returned home and evangelized the people. In his Homily on Pentecost, St. John Chrysostom mentions that the Ethiopians were present in the Holy City on the day of Pentecost.”[2]

The Ethiopian Orthodox Church was founded after a Christian philosopher and two relatives, Frumentius and his brother from Phoenicia (modern-day Lebanon), ran out of supplies and were stranded in the capital city of Axum. Frumentius helped spread Christianity in the city before being appointed the archbishop of the country. He converted the king and it became the state religion. “In fact, the EthiopianChurch exists today as self-governing, though it traditionally shares the same faith with Egypt’s Coptic Church. Until 1955, its Patriarch was a Coptic bishop sent from Alexandria, though that changed in 1959, and ever since then, a native Ethiopian has been the Abuna, or Patriarch. The main way that the Coptic Church is different from mainstream Orthodox Christians is that they believe that Christ has a divine nature in which the human nature is contained versus being two distinct halves.”[3] This belief has also kept them at arm’s length from Catholics and Protestants. “Wishing to stress that Christ has only one, simultaneously human and divine nature, the Orthodox Church of Ethiopia also refers to itself as the Tewahedo (also spelled tewahido), or “Made One / Unity,” Church.”[4]

Christians in Ethiopia have had their faith tested by the Muslims, who controlled Ethiopia from the 7th – 16th centuries. Today Muslims make up 25-40% of the Ethiopian population. They have also tried to protect themselves from other Christians – the Roman Catholic Church tried to bring them into the Western communion with the help of the Jesuits – but failed. The Catholics tried again during the time of Mussolini, but this attempt failed as well.

The language spoken in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church is Ge’ez, which is a Semitic language, like Hebrew and Arabic. Unlike these two though, it is written left to right instead of right to left. Few people outside of clergy understand Ge’ez and nowadays, most services are conducted in Amharic, the official language of modern Ethiopia. “Today the Ethiopian Church is unique among Orthodox communities in several respects, including the use of drumming and liturgical dance and the continuance of Jewish practices such as circumcision, the observance of dietary restrictions, and the keeping of the Sabbath.”[5] The church came to America officially in 1959 after the Abuna of Ethiopia was officially recognized as the Patriarch of the Church, but has since drifted away from the MotherChurch in Africa.

Icons have long been a tradition in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, as they are an important visual representation of the scriptures. Painting of books and manuscripts started as early as the 6th Century CE, though mass production of icons didn’t start until the 15th century, after a change in church liturgy occured. There were icons produced prior to that, but none have survived. The most productive time for Ethiopian Orthodox icons was the 17th and 18th centuries. “Thematically, Ethiopian iconography was strongly influenced by Byzantine models; later Ethiopian art also reveals the influence of Western religious painting. Nonetheless, the vibrancy and simplicity of Ethiopian iconography mark out a distinctive style in the history of Christian art.”[6] Like in Western churches, patrons paid for commissions to create the icons and donated them to the churches. “Stored with other sacred objects, icons were displayed on holy days and in public processionals. [This is also the case with the Tabots, the replicas of the 10 Commandments, which each church has in their sanctuary.] With the donors’ hopes of obtaining divine intercession, images of Mary, the Mother of God, are understandably the dominant theme.”[7] Large icons were created to be used in church processions, while smaller ones were created to be carried around by individuals such as the ones in Glenna’s collection.

Each icon is painted on either paneled wood or goat skin. They have a base layer of white paint called gesso, which is put down before any actual image painting starts. Originally the paints came from natural sources, such as minerals, plants and clay. Later on, because of their extensive trade with European countries, the artists used manufactured paints.

Although Ethiopian and Byzantine iconography is very similar there are some differences. The Ethiopian icons use a wider variety of bright colors, there is no use of gold in the backgrounds, there is rarely any text and the saints and other holy figures frequently have painted rather than golden halos. They also tend to depict the Trinity, which is not encouraged in the ByzantineChurch. “Among the more favored subjects of Ethiopian iconography are the Flight from Egypt (as a reminder that Africa sheltered the Holy Family); St. George, the patron of Ethiopia, who is often seen close to Mary; Mary and the Christ Child flanked by angels; St. Michael the Archangel; the Nine Saints, who are often depicted in a circle; various events from the lives of Mary and Jesus; and Ethiopian saints, especially Takla Haymanot from the 13th century.”[8]

Ethiopian Orthodox crosses follow four basic styles: Axumite (from the ancient capital city of Axum), Lalibella, the Star of King David and Gondor. “However within these basic four styles, there are hundreds of design variations for the main types of crosses, i.e. the large Processional Crosses used for church service, the Hand Crosses held by Priests and used for blessing the laypeople, the small ‘Cross Toppers’ for the church prayer sticks or rods used by Hermit Monks (called Batawe, who travel the country in constant prayer). There are also Pendant Crosses worn by the faithful.”[9]

[1] Taken 6/20/13 from Betsy Porter at: http://www.betsyporter.com/Ethiopia.html,

[2]Selassie, Sergew Hable and Tamerat, Tadesse. “The Church of Ethiopia: A Panorama of History and Spiritual Life” Addis Ababa: Dec 1970. A publication of the EOTC. Taken 6/7/13 from: http://www.ethiopianorthodox.org/english/ethiopian/prechristian.html

[3] Taken 6/7/13 from the Imperial Family of Ethiopia at: http://www.imperialethiopia.org/religions.htm

[4] Taken 6/14/13 from Michael S. Allen at: http://pluralism.org/affiliates/student/allen/Oriental-Orthodox/Ethiopian/EthiopianChurch.html , 2005.

[5] Taken 6/14/13 from Michael S. Allen of the The Pluralism Project at: http://pluralism.org/affiliates/student/allen/Oriental Orthodox/Ethiopian/EthiopianLangAndCulture.html, 2005.

[6] Taken 6/14/13 from Michael S. Allen of The Pluralism Project at: http://pluralism.org/affiliates/student/allen/Oriental-Orthodox/Ethiopian/EthiopianIconography.html, 2005.

[7] Taken 6/14/13 from Bryna Freyer, National Museum of African Art at: http://www.nmafa.si.edu/exhibits/icons/faith.html, 2003.

[8] Taken 6/20/13 from Wolfsbane at: http://thesaurostesekklesias.blogspot.com/2012/02/iconic-icons-supplement-ethiopian-icons.html, 2012

[9] Taken 6/20/13 from Emahoy Hannah Miriam Whyte of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church Info at: http://www.ethiopianorthodoxchurch.info/PhotosOfCrosses.html, 2008.

You must be logged in to post a comment.